Machines of Loving Grace: What is the Signapse approach to Artificial Intelligence (AI)? - Myths about AI and real risks

The phrase Machines of Loving Grace comes from a 1960s poem by Richard Brautigan. It imagines a future where technology works harmoniously next to nature, enhancing human lives rather than dominating them. It is also referenced, sixty-five years later, as recently as October 2024 by Dario Amodei, the CEO of Anthropic in his blog. Both are powerful pieces, that echo deeply with our people and what we do at Signapse.

For Deaf communities, the stakes are high. Our vision is to translate all the world’s words into sign language using Artificial Intelligence. Accessible communication is a fundamental right, and poorly implemented AI runs the risk of increasing rather than decreasing exclusion.

This article, by Deaf Journalism Europe, based around very early tech in Germany, explains this well. We get this, which is why we are building tools that align with the values and needs of the people they serve. I’d like to talk about three of the biggest myths around AI and sign language and attempt to debunk them.

Myth Number 1: The robots are coming

When the public thinks of AI, they often picture robots with minds of their own, which to be frank, is a little scary. This idea in the public consciousness, this “meme”, comes from pop culture rather than real-life. From 2001: A Space Odyssey and Isaac Asimov and the IRobot series, through Her and Ex-Machina to The Terminator and that awful robot dog in Black Mirror, these stories often talk to something deep inside for us.

And I think one of the reasons for the “robot” idea is because AI is really hard to show examples of, to illustrate what it looks like. Should we use just a picture of a computer or a bank of data? This is what computer servers really look like, is this what will help us understand?

So we love the idea of the robot from The Terminator cos it is easy to show what AI could mean, what it could do and what it could look like; we have a biological attraction and affection for things that look “like us”. 40% of the articles about AI I have seen recently have this sort of image below. (The other 60% have those “stars that stretch out to space and twinkle” if you have a nice marketing budget).

So, we see in the press and on the internet, these very inaccurate and misleading pictures and they make us worry. We get concerned about so-called “unfriendly” or “unaligned AI”. Unaligned AI means technology whose goals are not matched with those of humanity and, in our case, the Deaf Community. So, the robot is a deeply unhelpful picture for us and it is doing us a disservice, as it has become a cultural shorthand for very deep fears around unaligned AI.

And these fears also oversimplify the nature of AI. As ethicist Luciano Floridi aptly put it:

“The problem is not HAL (from 2001), but HAL: Humanity At Large. The risk isn’t artificial intelligence, but human misuse of it.”

Floridi’s words remind us that AI lacks moral agency. It cannot "decide" to harm or help - it follows the goals set by its creators. When biases or failures occur, they reflect human decisions, not machine malice. The critical point is, of course, that AI does not have a mind of its own. So making sure that we use what we have created as “tech for good” is really in our hands.

Myth Number 2: We are replacing human translators and interpreters

Signapse makes tools that amplify human capability not replace it with fake people. Only 1% of digital content is translated at the moment - there are 1500 registered translators and interpreters in the UK, which would need to increase to 150,000 if we wanted to deliver our vision using people.

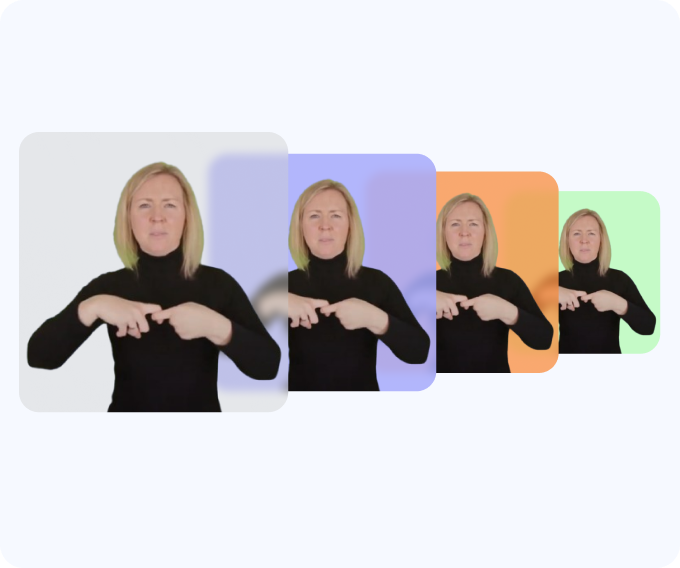

We aim not to anthropomorphise (turn computer code into real people) AI but to focus on how useful it can be. I prefer to describe our approach as "augmented intelligence" rather than artificial intelligence. The Signapse ethos is about working with Sign Language translators and interpreters, Deaf consultants, Deaf staff and our Deaf Advisory Board. We also provide ongoing remuneration to all Deaf translators whose image we use to generate sign language. We provide our services to clients that use Sign Language to create solutions that reflect their needs, respect their culture and will deliver a language that is clear and understandable.

And our products help scale relatively repetitive translation tasks, allowing human translators to focus on areas requiring cultural nuance and emotional intelligence. The idea of replacing human interpreters would be a very misguided and counterproductive one on our part. Our best outcomes come from collaboration between AI and human experts.

We’re also aware of the limitations of our current AI technology. That’s why human oversight remains critical, especially when precision and cultural integrity matter most. As an example, let’s look at “Redcar” a town in the North East of England - do we translate it as “Red” and “Car” or use the proper sign name that local people use. Once spotted by humans through our quality control process, we’ll make sure the correct sign every time.

We are working towards a world where our technology handles high-volume, low-stakes tasks - freeing human translators to focus on contexts requiring sensitivity or that are high-risk. No-one wants a piece of software to help them give birth, do they?

Myth Number 3: AI technology will be released with no guardrails

Another worry is that AI technology will be implemented autonomously, with free reign to provide services and make important decisions. The fear of autonomous agents with no human oversight is valid, as it is difficult to see the reasoning behind an action an AI agent has taken. As AI is developing, there has been parallel development of AI guardrails and alignment, the ideas that humans can place restrictions on the AI’s actions and stop them doing anything potentially harmful.

Specific to AI BSL translations, this fear manifests as “Are the automatic translations high-quality?” and “Are the generated BSL videos understandable?”. At Signapse, we are conscious of this fear and conduct many consultations with the Deaf community to get feedback to these questions. However, we understand the complexity of BSL and appreciate the difficulty in generating high-quality translations fully automatically.

That is why we conduct extensive manual checking and quality control of our AI translations. Multiple human translators and BSL-users are involved in the translation process, with a focus on the grammar used and the understandability of the final output. As our AI translation follows a two-step process (English -> Gloss -> BSL), it is easy to insert a manual check on the BSL grammar before the final BSL video is generated.

Before any translation is delivered to a client, it goes through a quality control process. At least two internal Deaf staff rate the translation for comprehension, with release only if a required rating threshold has been met. If a translation is rejected, a human reads the feedback and makes any necessary changes in the grammar to improve the BSL understanding. We know this process is necessary, and will be followed until our automatic translations have reached an acceptable quality level.

So, how do we manage the real risks?

The broader conversation about AI regulation also informs our approach. The EU’s AI Act, for example, provides a useful framework for assessing risk and ensuring accountability. Also, the SAFE AI Taskforce has a Deaf Advisory Group on AI and Sign Language Interpreting that we will be supporting.

By aligning with international standards, we commit to ethical development practices that prioritise human rights and community well-being. We adhere to three guiding principles:

- User-Centred Design: Collaborating with Deaf users and translators to ensure our tools meet real-world needs.

- Transparency: Openly sharing how our AI works, including its current limitations and future potential.

- Continuous Improvement: Learning from feedback and minimising risks through rigorous testing and quality control.

In Conclusion

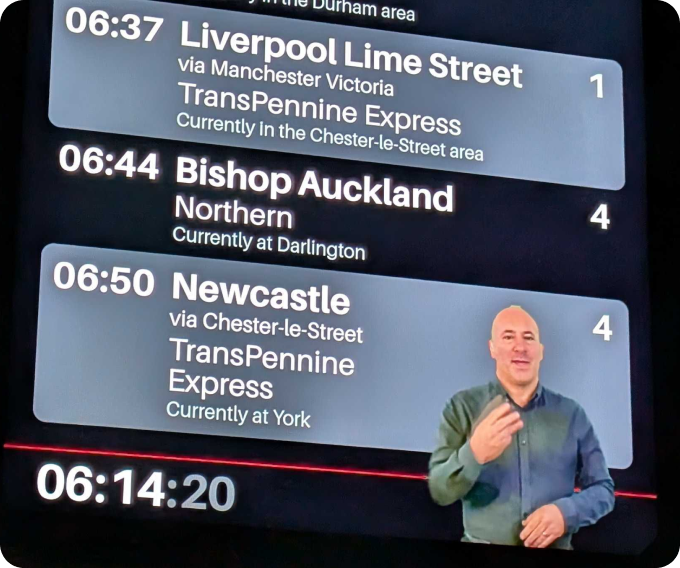

Our technology doesn’t understand love, grace, or even what a cat is. But it can help translate a government document into sign language, ensure a Deaf commuter catches their train, or bring a digital video to life for a Deaf staff member. The risks are real, but so is the potential. By aligning technology with human values, we can build a future where machines truly are tools of loving grace.

Related Articles

The Ethics of AI in Accessibility: Where Do We Draw the Line?

The Importance of Cultural and Linguistic Awareness in Sign Language Technology

Signapse's Sign Language Translation using Generative AI: Achieving Photo-Realism and Accuracy